Smart Healthcare Trends: Part 4, Implantable Medical Devices (IMD) and Wearables

Thu, Aug 17, 2017For Part 1, 2, and 3 in this series where I look at trends in Smart Healthcare please click here, here and here.

Implantable Medical Devices (IMD) and Wearables

Another field that is gaining in popularity, albeit in a somewhat niche market, are implants for convenience. Kevin Warwick has been a long-term proponent of augmenting the human body and his 2006 paper details his experimentation with a surgically implanted RFID (Radio Frequency Identification) device. This implant allows for user identification, movement detection, and automation, and enables the Smart Environment around him to react to the presence of the user. While being an extreme example, it can be argued that Warwick’s research in this area has broken new ground. It is now common to see transitory implantables in the form of ingestible devices that can measure everything from the level of acid in the stomach to blood alcohol level. This latter information could, for example, be used to enable or deny access to a vehicle by the home owner. Implantable devices will continue to be the focus of attention in the coming decades. We are much more likely, in the short-term at least, is to see an increase in the use of wearable devices.

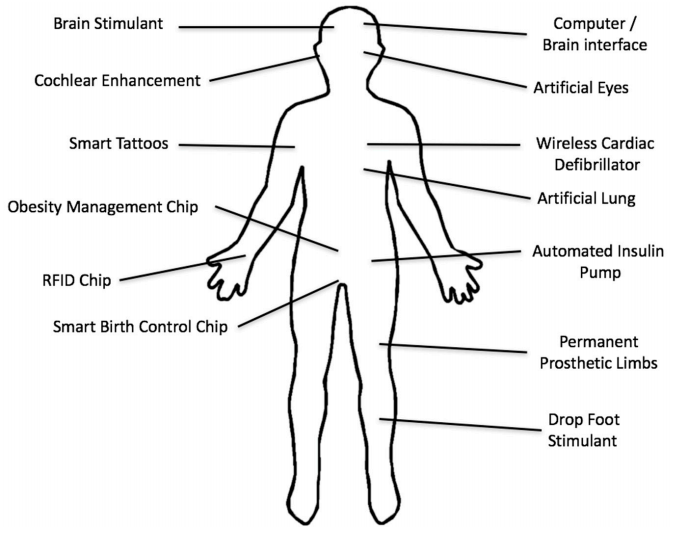

The diagram below shows a number of implantable sensors and where they are located in the body.

The demand for wearable devices has increased dramatically over the last decade and, according to Juniper Research in 2014, the wearable market is set for a more than 10-fold increase in hardware revenue alone by 2019. Wearables cover a wide range of uses such as lifestyle sports and fitness, entertainment, healthcare, and enterprise, with the current surge in awareness particularly focused on the former two, spearheaded by companies such as Fitbit, Apple, and Jawbone. While originally these devices performed simple operations, such as tracking the number of steps a wearer performed throughout the day they are now becoming more sophisticated. Most consumer wearables do not employ medical-grade sensors but devices such as the Apple iWatch can interoperate with medical-grade add-ons such as the Kardia Band which can be used to detect Atrial fibrillation, the leading cause of strokes. It is expected that the lines between traditional medial-grade devices and consumer health and fitness devices will continue to blur especially for use-cases including monitoring heart- and blood-related data. Fitness trackers will also continue to be the subject of clinical trials focused on weight-management, obesity, diabetes, cancer, and more.

The work by Zhu and others on correlating physical activity with mood is particularly interesting. The researchers use only off-the-shelf components, in this case the Pebble Smart Watch and an Android Smart Phone, to advise the wearer based on predicted mood. What makes this research unique is the fusion of activity tracking detection and mood inference engine that can use perceived mood such as “stressed” to try counter that by suggesting an anti-stress activity such as exercise based on heuristic data. Similarly, the software can correlate the activity with the mood so if “shopping” results in the wearer being in a bad mood this data can be used to predict future moods based on activity and advise accordingly. This fusion of data and interpretation holds promise for future research.

The environment could provide energy for wearables as well, for instance, it was reported that circularly polarised textile antennas could transmit power. Furthermore, sensors, which harvest energy from nearby health monitoring bands has been implemented. Moreover, radiofrequency (RF) energy harvesting antenna in a wearable sensor was introduced by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Current devices can generate energy from both a body and environment, but further development is required to harvest more power.

Research opportunities are present in data-mining the vast quantities of information that wearables generate, especially when it comes to detecting anomalies in individuals and in statistically-relevant groups. Apples initiative here with their ResearchKit and CareKit hint at innovation at a massive scale, enabling field trials with millions of individuals. There will be further research opportunities around combining data from several sensors to form a holistic picture or a wearers health and how that is affected by external factors such as weather (seasonal affective disorder (SAD) detection), amount of exercise (exercise-related endorphin boost), social interactions (GPS, Bluetooth, proximity data, and social media), TV viewing habits, or even a person’s income level. Hardware sensors will continue to be miniaturised and become more viable as they are embedded into all-day, every day accessories but research needs to done to improve the battery life of these devices. Typically, something such as an Apple iWatch lasts around a day of normal usage, a Fitbit Charge up to 5 days, but this will have to improve especially when consumers are used to watch-like devices lasting much longer.